No one should say, “If we lose <INSERT NAME>, we are in so much trouble.” Consider a championship football team. There are only 11 players on the field at any given time representing a team. However, whether collegiate or pro, the roster has 105 or 53 players, respectively, providing a certain level of depth. While losing the star quarterback is never an ideal situation, a team still has the capability to perform. For whatever reason, many construction organizations appear to consistently run a personnel deficit. As a full disclaimer, it is understood that a professional football team has a different payroll and revenue structure than a normal construction firm. However, for all the bluster on the enormous salaries and payrolls, they are consistent and relative with the competition, and there is also a salary cap in place to maintain a level of competitiveness.

Now consider a construction organization. Regardless of the revenue, every “player” is playing the game. If there are 10 project managers, there are 10-plus projects that each manager is married to. If one of those managers were to leave — voluntarily or involuntarily — the fragile balance would be disrupted. The organization can certainly find a free agent in the market to replace the former player, but there are concerns about learning the operational playbook on short notice, cultural assimilation, etc. One of the worst scenarios has an operational leader — CEO, president, chief operating officer, director, executive, etc. — taking over for the void. What often begins as a stopgap measure often becomes a long-term proposition. This is the equivalent of the head coach suiting up to fill in for an injured quarterback. Not sure about you, but I might be interested to see Andy Reid filling in for Patrick Mahomes instead of filming silly insurance commercials.

A Case for Bench Development

So, should we have four project managers riding the pine while the balance of the team runs work? In an ideal world, each manager or superintendent would have a backup, but in an extremely delicate economic model like the construction world provides, the backup will be an understudy.

For instance, great organizations have progressively feathered in the role of the project engineer. The challenge is balancing that position’s role as a support player and continuing the development of that future generation of project leaders. In most cases, the best source of bench strength comes from within in the form of “rookies.” Great firms create a model that allows for this less experienced cadre of associates in the form of the following:

- Mentorship — There has to be a feedback mechanism that creates an ongoing dialogue about everything, from performance to simply being a sounding board.

- Deliberate training — Training is not just a one-off event that occurs annually but rather a systematic program that supplements learning throughout a career.

- Career progression — How does that rookie get an opportunity to play in the big leagues? How does one continue to take steps up the ladder?

Strategic Building

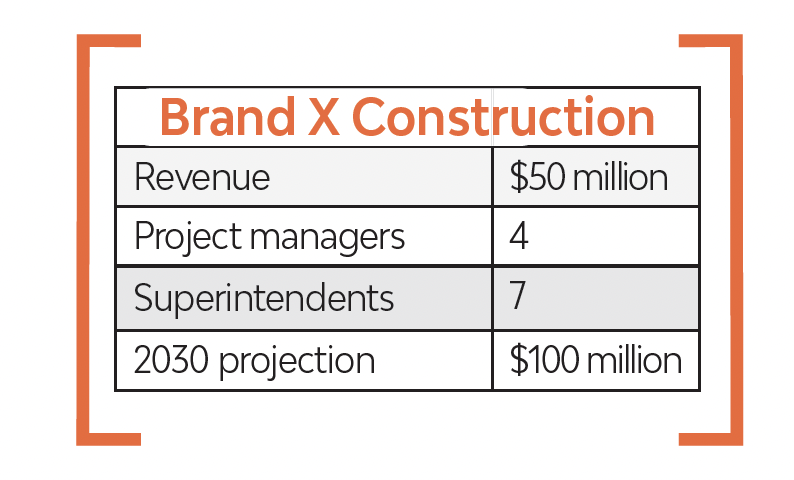

So, you want some modicum of growth by the year 2030, but you haven’t thought through the staffing considerations yet? Consider this scenario:

There certainly is an argument to be made that the firm needs at least four more managers and seven more superintendents. The firm could certainly aim to simply do higher revenue spread over the same number of projects annually (i.e., larger project size), but for this case we can assume a constant project size. Now consider this: What if the firm historically has an attrition rate of one manager/superintendent a year? In reality, the team will need eight managers and 14 superintendents at a minimum. This also does not allow for promotions, retirements or successions. If this firm simply does the bare minimum in its hiring/development goals, it will be holding serve and barely addressing the strategic side of the business. The smart leaders realize that strategic growth is not just about securing more work but being a firm that makes talent acquisition and talent development the hallmark of their long-range strategic plan.

Additionally, we have to look at one of the fallacies of bench strength: If a firm has the people, they will use the people. For instance, what if they hire a junior manager with the intention of that person being a development project? But what if an unanticipated project comes over the transom? Rather than being disciplined and acknowledging a scarcity of resources within the firm, leaders quickly take the project, retorting, “Well, we have to cover these costs.”

Think about a football team — they land an amazing draft pick and immediately think, “I guess we plan to run plays with 13-14 players each play.” It is one thing to provide that rookie a few plays as a developmental tool, but it is another to drop them in the middle of a game — and perhaps a losing game — just because.

The good news is that revenue is growing, but at what cost? The bench is back to zero depth, and a rookie is thrust into the role of “starter” overnight. It is certainly not an easy feat to balance backlog in a world of slipping starts and kickoffs.

On the other hand, too many leaders view bench depth as a sign of weakness or being idle. It is one thing to insert a project engineer early because of a surprise resignation, but it’s entirely different than finding a project for that engineer so they can earn their keep.