Compensation can be an icky subject. While “icky” might be the least technical adjective to use, many business leaders feel their skin crawl as the topics of base compensation and bonuses enter the conversation. Employers feel that compensation is one of the main impediments to attracting top talent, while employees simply want what they feel is fair in the market. With dynamics like this, what could possibly go wrong?

For many years, FMI Corporation has studied the myriad compensation programs that exist. And if there is one inalienable truth, it’s that there is no perfect program. Designing a compensation program requires care and an affinity to align the right drivers with the right outcomes. However, leaders must first identify the rocks in the road that are directly affecting their current system.

There is plenty of data and resources in the market that give business leaders the ability to determine effective wages and salaries for most positions. While there is always some subjectivity when it relates to job titles and descriptions, this is less about the base compensation and largely about the 500-pound gorilla in the room — bonus programs.

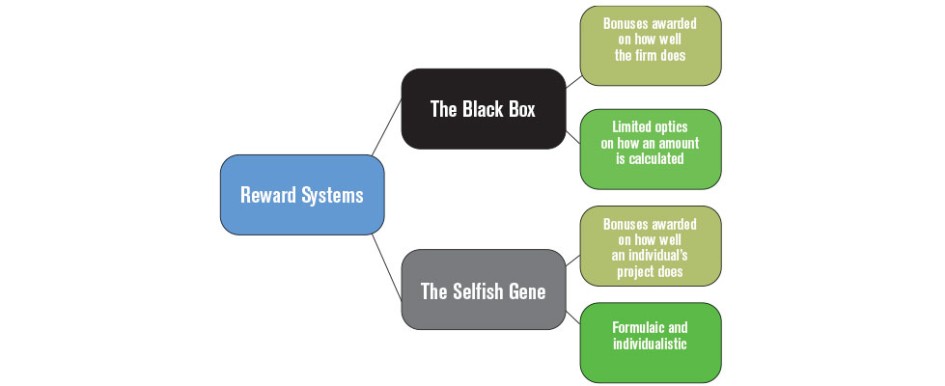

For a large percentage of organizations, there are two basic bonus philosophies: the Black Box and the Selfish Gene. These programs (Figure 1) come with a fair bit of cynicism, but they do begin to describe the challenges that a firm faces when fairly compensating business units, project teams and associates.

The Black Box

The concept is simple. If the firm does well, the team does well. Win together, lose together. The calculation is often straightforward, requiring little more than the firm’s roster, base salaries and a spreadsheet. The challenge comes when a firm tries to use the bonuses to drive individual behaviors. With limited optics on how the calculation is made and the timing on which the bonus is made (i.e., normally coinciding with the holiday season), associates of the firm tend to view this less as a performance incentive and more like a gift. As a result, employers often characterize the attitudes of their associates as entitled and ungrateful. The questions to ponder are this:

- Is the firm truly sharing the fruits of a successful year? Is the perception of a “gift” correct?

- Is the firm trying to modify behaviors and engage the team better by using the bonus as an incentive?

There are several unintended consequences that occur. First, if a firm is bonusing everyone equally, using the base salary as the foundation for any calculation, how does it reward high performers effectively? In many cases, there exists a high level of “bonus socialism” that occurs in this system, in that everyone receives the same percentage. Or worse, there is a perception that everyone receives the same percentage because of the “Black Box phenomenon.” Ultimately, the firm has the potential to create a “free rider effect.” Top performers are demotivated by everyone receiving the perceived same amount and lower performers dig into their behaviors because they receive something regardless of performance.

The Selfish Gene

There is a great migration that often occurs when firms try to swing the pendulum after receiving critical feedback on a negative “Black Box experiences.” Rather than pay everyone similarly, firms compensate project teams based on the performance of their individual completed projects. Paying for performance seems like a logical transition. Perform well and you get compensated well. However, this method requires two big considerations:

- How the work is doled out.

- Alignment of customers/markets with individuals within the firm.

Like most organizations, leaders put their best people on the most complicated projects. In some cases, these projects may have inherent flaws such as estimating errors. Through no fault of the manager and superintendent, they are responsible for completing a project that was at risk from its inception. At the end of said project, what if the margin is zero?

Conversely, what about that project that was assigned to an associate that had all the makings of a perfect project? Fat estimate, heavy contingencies and seemingly pristine conditions to build — through no achievement of their own, they are rewarded disproportionately.

Fool me once, shame on the firm. Some managers and superintendents work to solve for this on their own. Frugality gives way to the Selfish Gene, creating situations of hoarding and not firm-first behaviors. Rather than sharing and supporting a colleague, a manager or superintendent might take a more aggressive stance when it comes sharing equipment, tools, people, information, etc. The good news is a project may win but a firm may lose in numerous other areas including but not limited to the potentially toxic culture. Rather than having a united and collegial firm, there is the possibly of having a group of rogue individuals solely motivated by their own W-2.

The Happy Medium

So, the Black Box created free riders and the Selfish Gene mutated our organizations into a bunch of self-centered jerks. While all systems have their own flaws, there is a happy medium that can drive a win-win solution. Performance-based compensations systems do not need to solely be measured on how a manager’s projects perform, but, rather, how they themselves perform. Recall the example of a great project team assigned to a poor project. Assuming the firm does achieve some modicum of success, and assuming the project team does their best in managing that challenging project, they should be rewarded accordingly. Consider whether the manager exhibited the following traits when evaluating their performance:

- Operations – Did they follow the firm’s process procedures, resulting in higher performance?

- Client management – Was the customer pleased with the project?

- Safety – Was safety managed effectively and without issues?

- Good of the order – Does this person put the firm ahead of personal interests?

Regardless of the calculation or percentage, the firm sends a clear message about what is expected from every individual from both a qualitative and quantitative perspective. Additionally, superstars can be compensated proportionally and see the specific triggers that enabled them to see success.

Any compensation conversation is hard to have, but aligning a firm’s strategy, its operational capabilities and a measurable reward system is essential to long-term success.