Former United States Secretary of State John Foster Dulles once said, “The measure of success is not whether you have a tough problem to deal with, but whether it’s the same problem you had last year.” Indeed, we deal with the same issues or problems over and over. But why? The answer is simple, but it’s not easy: you failed to take the time to either determine the root cause of the problem, or you failed to implement a corrective action plan to prevent recurrence. Either of these will lead to a problem that continues to return. Unlike an extended yo-yo, which requires some skill to return to its starting point, problems don’t necessitate any true talent to occur.

What is Root Cause Analysis?

The key to a good root cause analysis is truly understanding it. Root cause analysis (RCA) is an analysis process that helps you and your team find the root cause of an issue. RCA can be used to investigate and correct the root causes of repetitive incidents, major accidents, human errors, safety near-misses, quality problems, equipment failures, medical mistakes, production issues, manufacturing mistakes, delivery delays and environmental releases, and can even be used proactively to identify potential issues.

The key to successful root cause analysis is understanding a process or sequence that works. The effect is the event—what occurred. A cause is defined as a set of circumstances or conditions that allows or facilitates the existence of a condition an event. Therefore, the best strategy would be to determine why the event happened. Simply put, eliminating the cause or causes will eliminate the effect.

First, though, you must weed through the symptoms (a sign or indication of the existence of something). Figure 1 provides an example—a puddle of hydraulic fluid on the floor. The puddle is a symptom of a leak, but the leak could be the symptom of a loose fitting. Wiping up the puddle of hydraulic fluid did not eliminate the actual cause. Therefore, the leak will continue to occur. The key to prevention of recurrence is determining the actual root cause and correcting it. The challenge is identifying the correct cause(s) of an issue.

A contributing factor is a condition that influences the effect by increasing the probability of occurrence, hastening the effect and increasing the seriousness of the consequences. But a contributing factor will not cause the event. For example, a lack of routine inspections prevents an operator from seeing a hydraulic line leak, which, undetected, led to a more serious failure in the hydraulic system. Lack of inspection didn’t cause the effect, but it certainly accelerated the impact.

The absence of binoculars in the crow’s nest of the Titanic did not cause the ship to sink, but it did contribute to the series of events that eventually led to the ship’s demise. In other words, the binoculars would have possibly allowed the lookout to spot the iceberg much sooner than unenhanced vision did for him/her.

All of this stresses the significance of approaching problems in a structured, systematic, logical process and provides a proven methodology to identify, analyze and verify the underlying root causes of recurring failures. The objectives for conducting a RCA are to analyze problems or events to identify:

- What occurred

- How it occurred

- Why it occurred

- Actions for averting reoccurrence that can be developed and implemented

Some basic drivers for an effective RCA include:

- Accepting more than one root cause for a problem or event

- Focusing on corrective measures of root causes as a more effective action than simply treating the symptoms of a problem or event

- Using a methodical process with conclusions backed up by evidence (facts and data)

- Enacting corrective countermeasures to prevent recurrence of issues, but also following up to ensure their effectiveness is critical

The "5 Why" Method

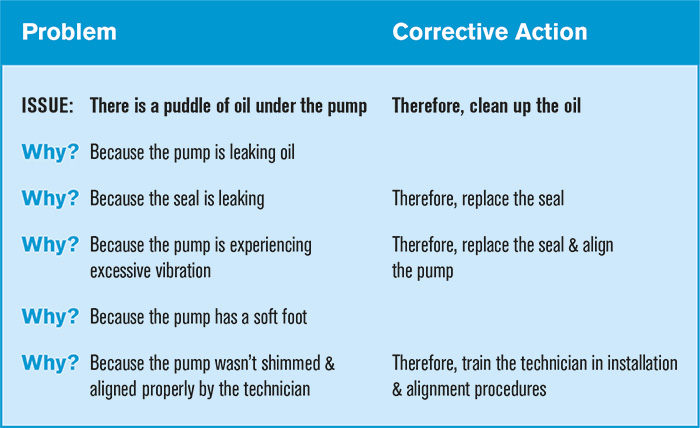

One method that has been around for many years is called the “5 Why” method. It is a simple, problem-solving technique that helps users get to the root of the problem quickly. It was made popular in the 1970s by the Toyota Production System. This strategy involves looking at a problem and asking “Why?” and “What caused this problem?” Often, the answer to the first “Why?” prompts a second “Why?” and so on—providing the basis for the “5 Why” analysis. The objective is to continue asking ‘Why?” at least five times, to get to the core of the issue. Here is a simple example:

- I didn’t get to work on time. Why didn’t you get to work on time?

- Because the car wouldn’t start. Why wouldn’t the car start?

- Because the battery was dead. Why was the battery dead?

- Because the dome light stayed on all night. Why was the dome light left on?

- Because the kids played in car, and then left the door ajar. Why did the kids leave the door ajar?

- Answer: Because I never stressed the impact of leaving the door ajar and the resulting drain on the battery.

- Solution: Explain to the kids what happens to the battery when the door is left ajar for hours at a time.

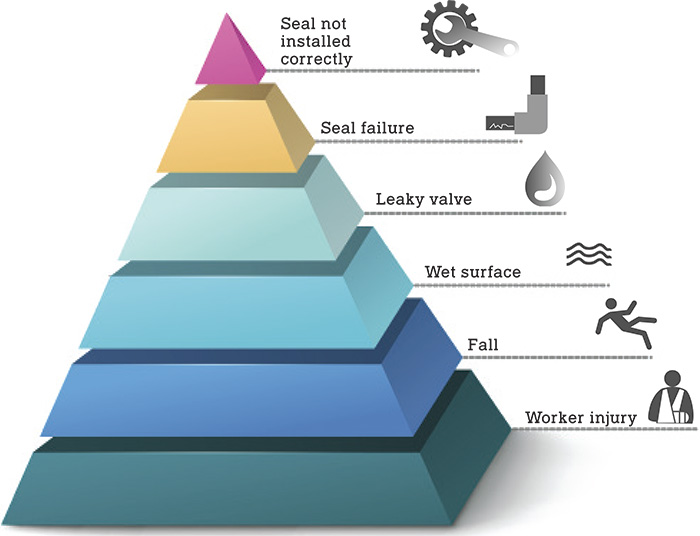

Figure 2 shows how properly identifying the levels of improvement—rather than jumping to conclusions or just treating individual symptoms—can potentially prevent larger problems in the future. Another issue in root cause analysis is jumping to conclusions too soon. We are often predisposed to the end results, whether or not they are valid. We jump to a conclusion without answering the fundamental question, “What is causing this to happen?”

RCA's Impact on Decision Making

Our experiences and paradigms tend to aim us toward certain solutions with limited underpinning in facts and data. In other words, we rely too much on intuitive decision making and less on rational decision making. Intuitive decision making is not baseless, but it relies less on analytical methods and more on experience and gut-level feelings.

Rational decision making uses facts and evidence, while intuitive decision making may be less grounded and more speculative. These types of feelings are instinctive and rely on intuition rather than actual facts.

In fact, intuition is the ability to have a grasp on a situation or information, without the need for conscious reasoning. People often use this type of decision making when facts are unavailable or when decisions are difficult. Some of the challenges in conducting an RCA include:

- Incomplete problem definition (too vague or broad)

- Lack of key participants on RCA investigation team (limited perspective)

- Missing key evidence (limiting on-site examination)

- Quickly focusing on solutions before understanding the root cause

- Limiting findings to one cause, when multiple ones may be the source

- Not finding the underlying or direct causes of an issue.

- Failure to investigate deep enough (need to keep asking why)

The bottom line is the problem will not be completely solved until the root causes are identified and the corresponding level of improvement is implemented.