Call it a guilty pleasure, but I have always been a fan of shows like “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” (pick your city) and “Castle.” The show begins with a victim being found by some unsuspecting character, and as the story evolves, the cast picks up various clues that lead them to a dramatic television conclusion. Of course, during the episode, there are several twists and turns leading the investigators down rabbit trails, sometimes directing them to the wrong suspect. After an hour of superior forensics (and television magic), we find out the butler did it.

Sometimes you see this same case played out in construction organizations today. There are certainly no dead bodies, but plenty of carnage — usually of the monetary variety. The question that rarely gets asked is this: Did the butler (or superintendent) really do it? Put another way, are leaders looking at the “murder weapon” and making incorrect determinations and decisions about a situation? Is their judgment clouded by something making the root cause difficult to determine? Below are several examples where a knee-jerk decision may have led to an incorrect assessment of innocence or guilt.

Case File 234 — The Curious Case of Equipment Gone Late

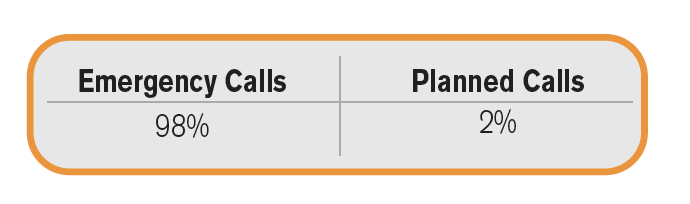

A large trade contractor has a shop/equipment manager (John Doe). This individual is responsible for all small tools, consumables and materials the field uses on their projects. After about a year, there is a growing sentiment that John Doe is “not performing adequately.” Superintendents and foremen are creating a massive amount of noise about how they do not get the things they need when they need them. Leadership is seriously considering a replacement for John Doe, but someone decides to conduct a brief investigation. John Doe is asked to track the calls he receives to the shop and evaluate if those calls are “planned” (items needed in greater than two to three days) or “emergency” (items needed in 24 hours or less). The table below is Evidence A.

It is also interesting to note that this organization operates in a large metropolitan area where traffic is an enormous problem. As the investigator digs deeper, it is determined that the entire field team does not utilize a short interval planning process that allows them to capture needs, crew sizes, issues, contingencies, etc. Simply put, when they need something, they call John Doe and only provide him several hours of notice. When he can’t make it happen, he is vilified.

Is the suspect guilty, or are the “victims” really to blame?

Case Closed: Superintendents are found guilty of improper planning.

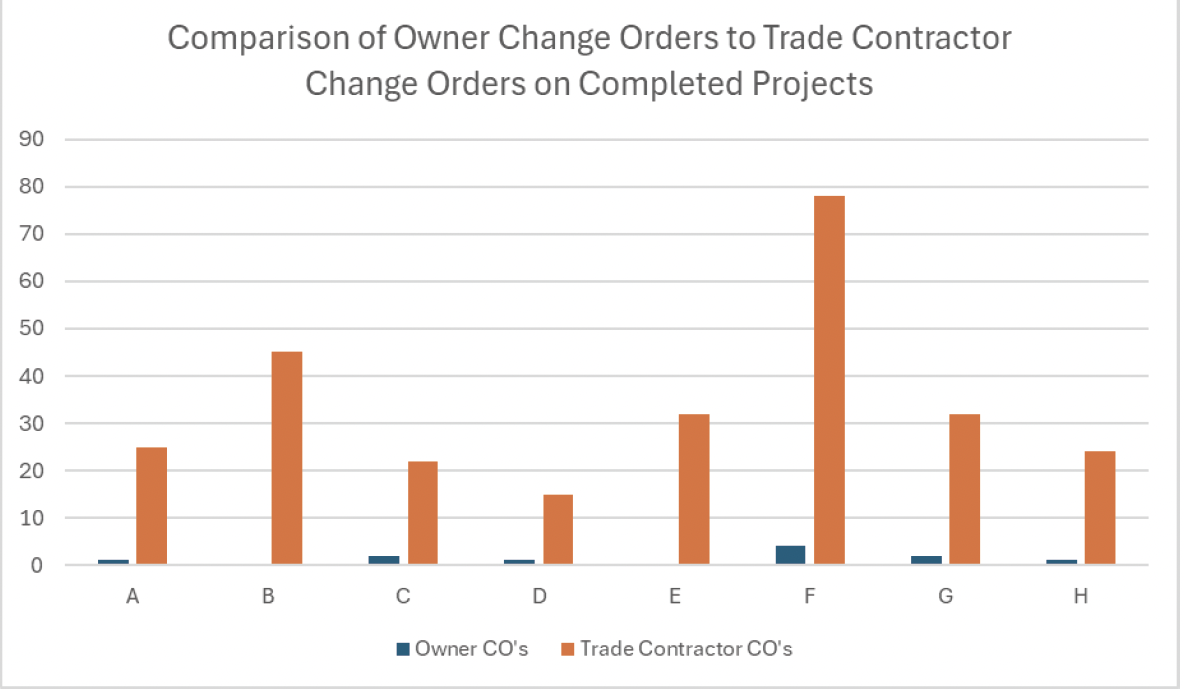

Case File 479 — The Case of the Change Order Never Asked For

A midsized general contractor (Doe Construction) is losing money. The theory is that they have bad customers who take advantage of them. They pride themselves for being extremely customer-centric, so much so that it is in their mission and vision statements. Customers do express a great deal of appreciation for how well Doe performs. However, the firm constantly writes down their projects. One of the leaders notices there are never any change orders in the system. In fact, there is a distinct lack of reporting when it comes to change orders globally. Yet as they dig deeper, these are all plan- and specification-type arrangements, normally characterized by errors and omissions. The graph below is Evidence B.

When questioned, project managers acknowledge the change orders but often reply with the following statements:

“Well, it was a little gray and we didn’t want the customer to be angry … ”

We wanted to keep the customer happy — isn’t that what we are about?”

“Sure, it was extra, but we made it go away … ”

Rather than deal with change orders fairly yet firmly, these individuals chose to acquiesce in the spirit of “customer service.” Some managers may have been conflict-averse while others wanted to look like the hero in front of the customer. Either way, the organization needed more structure that balanced customer-centricity and monetary protection.

Case Closed: Project managers were found guilty of not being project managers.

Case File 3.14159265 — The Case of the Project That Bled & Never Stopped

A midsized construction firm (Brand X) is losing money. More importantly, it always seems to be at the end of the project. As the leading investigators question the project teams about the end of the project, they hear some of these statements:

“We always finish on time.”

“We will never miss a deadline.”

“I’m not usually on a project at the end (I get shipped to a new project), but my assistant is the one on-site, and I’m sure they know what’s going on.”

There is a lot of evidence here. Now, it is admirable that Brand X never misses a deadline. However, what impact does that have on the project’s financials? In the mad dash to the finish line, does the firm throw money at the situation simply to get done? Additionally, what does the last statement say about how they finish? During the most critical time of the project, the person with all the knowledge is on to the new project, while their No. 2 keeps the seat warm. The correct answer is this: The firm should have an exit strategy to adequately plan the last phase of the work. If personnel are shifted, the entire team should conduct a “project exit strategy” to game it to conclusion.

Case Closed: Leadership was found guilty of failing to implement a firmwide project exit strategy

This is a tongue-in-cheek perspective on how firms sometimes make rash decisions based on a lack of evidence, or even a lack of perspective. The conclusion for you should be to consider how well you address root causes of problems and think through the appropriate solution.

If only we could fix all our problems in an hour.