Editor’s Note: This is the second article of a two-part series covering change order management. Part one appeared in Construction Business Owner’s September 2013 issue and can be found here.

Even with the greatest planning, changes during a project will occur. The RFI, or request for information, leads to the vast majority of work-in-process change orders. However, more often than not, the contractor knows the right answer to the RFI but poses the question in a convoluted way. RFIs become the documents that prove designer incompetence and offer one-upmanship for contractors with an ax to grind.

Rather than posing the right answer or conclusion to “lead the designer down the right path,” the contractor seeks to protect his or her interests, and the designer does the same. While change is inevitable, the contractor should proceed in a professional and clear manner to avoid antagonism and conflict among the project team. To facilitate a prompt and well-crafted response, an RFI should include the following:

- Location. Where on the site does the change occur? At what point in the plans does it occur? Sketches, cut sheets and photographs make visualizing the problem and potential solution easier.

- Potential solutions. What potential solutions are available? By suggesting options, contractors save time investigating solutions without assuming the risk.

- Magnitude. Does this change have a significant impact on the project’s cost and schedule? How is the cost quantified? For example, receiving clarification on wall colors has minimal impact, while resolving plenum conflicts with trade contractors may impact the schedule and project cost.

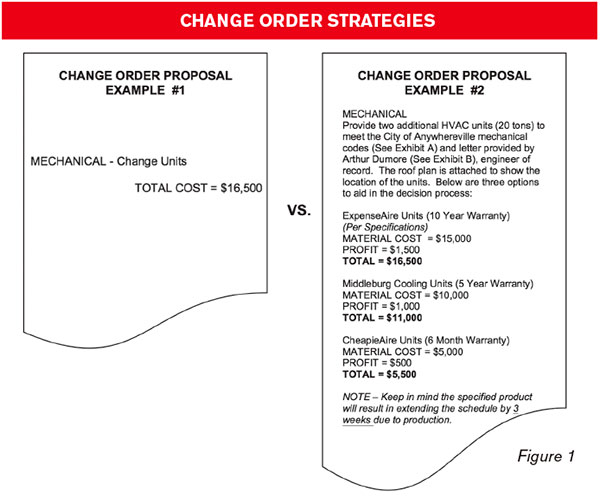

The same strategy is employed in drafting change orders. Receiving approval for valid change orders depends on how the change orders are presented. Consider the two examples in Figure 1.

When developing strategic change orders, first consider the audience. While a field director may understand the background illustrated in Example #1, decision makers further upstream may not be aware of important supporting details. Assuming the audience is ignorant of the change order particulars ensures project managers develop change orders that are easy to understand, as if they were educating their customer for the first time.

When developing change orders, project managers should understand that “sticker shock” is one reason for delays in change order approvals. While customers may be assured they want a particular product or system, they are often dissuaded after seeing the price tag. The knee-jerk reaction is to ask for other options. A detailed description of a change order will help eliminate a costly and unproductive step in change order resolution.

Another common issue with change orders is calculating all the components of the price. Arguably a contentious issue, margins are something contractors often avoid sharing. In the past, contractors could mark change orders up 40 to 50 percent, and customers wouldn’t bat an eye at the exorbitant costs. General contracts and subcontracts now often stipulate change order terms and quantify allowable margins and overhead. Make these details clear. The customer will undoubtedly ask for the specifics, and trying to hide this information can damage credibility. While change orders may lack the enormous profit potential of yesteryear, contractors should measure all the hidden costs of change orders.

As a change order is priced, project managers should review a checklist of potential change orders including, but not limited to, some of the items below:

- Additional supervision

- Additional project management (if direct costed)

- Cleanup

- Additional storage and trailer rentals

- Transportation costs

- Miscellaneous tool and equipment rental

- Bonds

- Builder’s risk policies

- Safety management and supplies

Many of these items are easily justified and imperative to completing additional work. Preparing the change and providing sufficient explanation make a change order more acceptable to the customer.

Lastly, avoid discussing a change order without evaluating its impact on a project’s schedule. Nothing is more frustrating than having finally agreed to a change order value, only to have a general contractor or trade contractor say, “Glad we got that approved. By the way, the materials you chose will take an extra three weeks to produce.” When making final decisions, customers often consider schedule more important than cost. With the modification of the scope of the work, contractors must reallocate resources by adding labor and equipment to accomplish the work or by extending the schedule and using existing resources. Many contracts have clauses that preclude the addition of time to schedules. Hard and fast deadlines mean the adjustment must be addressed during the pricing. Proposing change orders at standard rates when additional time is necessary is a recipe for margin fade.

Time and materials tracking is one measure contractors use when change order values cannot be agreed upon. Customers often believe this method ensures the contractor will not pad change orders with excess contingencies. However, some customers will still balk at the final invoice, dismissing weeks of work tickets, time cards and receipts because “there was no way it could have taken that much time or that many materials to do that work.” Who is at fault—the customer who had the option of taking the lump sum change order value but chose not to or the contractor who perceivably duped the system and used this time and material change order to capture lost margin? In the world of change orders, no one is without blame. Better communication during this process can reduce conflict.

One tool to help prevent sticker shock is the use of running time and material change order updates, which continually provide the customer breakdowns of the change order costs during the work. Frequency of updates is dependent on the project specifics. Some change orders will require only weekly maintenance, while others may require daily updates. Contractors should create a running time and material change order log so the customer can compare the progress to their baseline or expectations.

In addition to documenting the various costs and presenting them in a way that provides a chronological history, this log also will allow customers to quickly review reasons for projected cost overruns. In many cases, it resembles an abbreviated work-in-progress report for the customer. This log also assumes the field managers are receiving the appropriate daily approvals and gaining consensus on quantities and work tickets.

Proactive Measurement

Accurate record keeping provides a level of accountability and measures a firm’s risk as it relates to change orders. Numerous project management software packages contain tools to document not only change orders and RFIs, but also important metrics about a project’s or individual’s performance. One way to document this information is by using a project-specific change order log.

Change order logs measure a project’s metrics to gauge its successes or shortcomings. Establishing a change order closure rate provides a benchmark for unapproved change orders. In one scenario, change orders may typically close within 7.5 days, while the outstanding change orders average 10.8 days. Ticklers or metrics such as these serve as reminders to refocus and readdress the problems.

Understanding how change orders are affecting your business is essential if you want to make effective managerial decisions.