Construction remains one of the most dangerous industries to work in. According to a 2016 Bureau of Labor and Statistics (BLS) report, construction led all other industries in fatal work injuries at 991—a rate of 10.1 per 100,000 full-time equivalent workers.

To protect workers from injury, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) levies a full scope of safety regulations, ranging from procedures to the wearing of personal protective equipment (PPE). However, when it comes to the hazard of worker fatigue, there are no codified, statutory OSHA requirements set. As a result, worker fatigue goes underreported, and no formal mitigation strategies are developed.

Many industry experts believe that worker fatigue can be easily mitigated through work scheduling methods. Still, some believe it’s a condition of employment to which workers must adjust. Though there is some truth to both views, they do not account for the various hidden aspects of worker fatigue, namely its financial impact, its nature and scope, and its contributions to worker injuries.

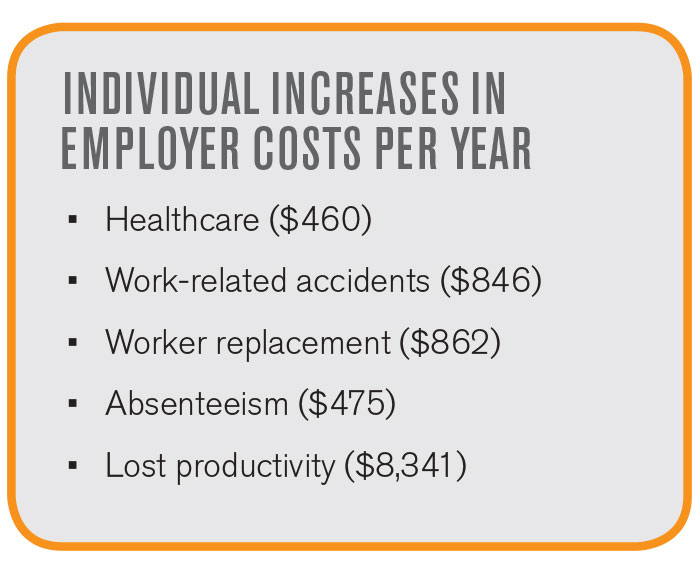

Financial Impact

According to the National Safety Council (NSC), the hidden costs associated with poor sleep (worker fatigue) cost the construction industry approximately $1.8 million per year on average.

The box to the right provides the individual increases in employer costs per year, based on a construction company size of 1,000 employees and a $2,000 average annual healthcare cost per employee.

Nature & Scope

In 2017, the National Safety Council (NSC) conducted a nationwide study on workplace fatigue, in which 2,010 adults working in varying industries and varying in age, gender, ethnicity and geographical location were included.

The study reported a 97-percent decreased cognitive performance in workers, showing that:

- 76 percent were tired at work

- 53 percent were less productive

- 44 percent had trouble focusing

- 39 percent had trouble remembering

- 27 percent had trouble making decisions

Along with these results, the study also revealed the percentage of respondents experiencing micro-sleeps (instances of nodding off) and where they took place.

- 41 percent off the job

- 27 percent on the job

- 16 percent on the road

The NSC results show two very critical features about the nature and scope of worker fatigue. The first is that fatigue, no matter the source (physical exertion, sleep loss or mental exertion), alters a person’s ability to perform mental tasks. This is clearly evidenced by the 1,950 survey participants (97 percent) who reported various decreases in their cognitive abilities while at work. This means workers are prone to various types of mental errors, showing the hazardous nature of worker fatigue.

The second feature is micro-sleeps, or instances of nodding off. The NSC results show that fatigue is prevalent both on and off the job. Twenty-seven percent of participants reported nodding off on the job, while 41 percent reported doing so off the job, illustrating that a constant state of fatigue is present. A cause for concern is the increasing degree of a worker’s fatigue when beginning a job and being on the job. This is the hazardous scope of worker fatigue.

Injury Data

According to OSHA, worker “fatigue is not a recordable contributor to an injury, incident or accident” and is, therefore, not considered a viable hazard. However, the best worker fatigue injury data is found in research literature.

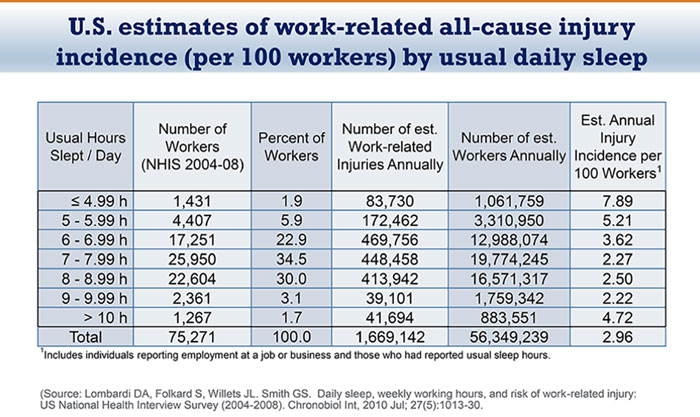

Researchers Lombardi and Simon Folkard of the Université Paris Descartes estimated work-related annual injury incidence rates using data from the National Health Interview Survey (2004 to 2008), which investigated over 75,000 participants. In their review, it was estimated that there is an annual rise in injury incidence rates per 100 workers when workers receive less that 7 hours of sleep. See more data from this survey in Figure 1.

The Necessity of Sleep

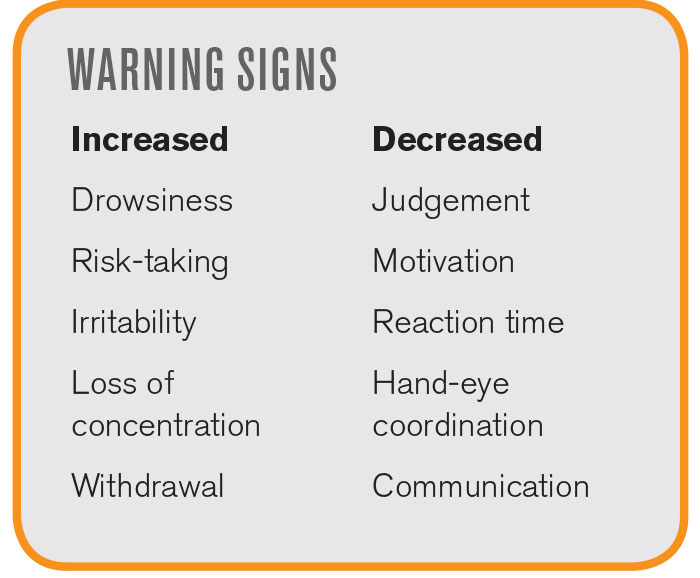

Sleep is a biological necessity—a time reserved for the body to perform a host of vital physical and mental maintenance functions. When both functions are fully satisfied, the body produces a physically restored and mentally alert person. When sleep is disrupted, the body responds by sending out a number of different warning signs, alerting that more sleep is needed.

The contributing factors that disturb sleep include mental or emotional stress, medications, short- or long-term medical conditions, work-induced factors (e.g., shift work, long hours or weeks) and unrestful lifestyle choices. If the proper amount and quality of sleep is not present over a period of time, the constant state of tiredness known as fatigue will result. Unfortunately, many learn to ignore these signs and continue life as normal, whether at work or at home. This is dangerous, as most of us are very poor judges of how fatigued we truly are. As a result, we are unable to determine how unsafe we may be, especially at work. The National Sleep Foundation (NSF) recommends that adults ages 18 through 64 receive at least 7 to 9 hours of sleep per day to be fully rested and alert. Typically, we receive less than the recommended amount. In a study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), around 180,000 workers, representing different industries, were surveyed over a 2-year period. The results show that approximately 38 percent of workers, ages 18 to 54, receive less than the recommended 7 hours of sleep per day.

Jobsite Risks

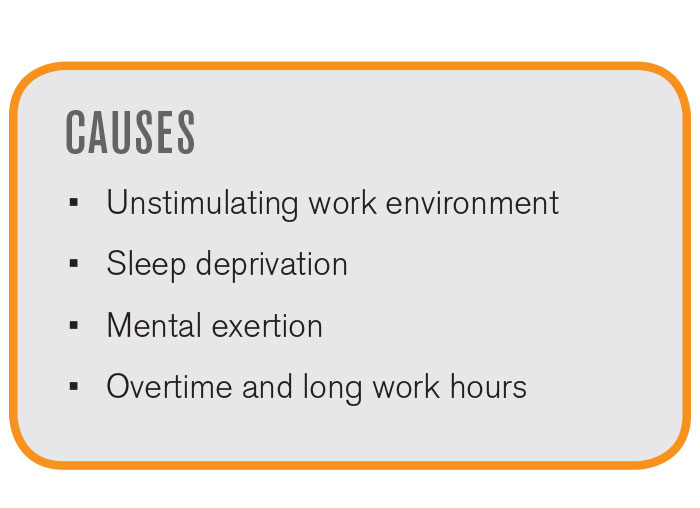

Matthew Hallowell, an associate professor of construction engineering at the University of Colorado Boulder completed a literature review of the causes and outcomes of occupational fatigue. He concluded that industries at the highest risk are those where people are working long hours, overtime or many days in a row, while exposed to harsh environmental conditions, such as working in the rain or snow.

Industry veterans know that as a construction project draws closer to completion, the effort put into installing building systems on site (electricity, plumbing, HVAC, etc.) becomes more complex. Typically, this makes workers more prone to injury, as they must work with and around other tradespeople. When fatigued, the chance of injury increases as the focus shifts to completing the job, and personal safety is often ignored.

Construction sites are busy places, in which equipment, vehicles and cranes are in continual motion. To be safe in this hectic environment, workers must focus on their tasks and also be situationally aware of their surroundings. This requires a certain level of attention and awareness, especially for machine operators. When fatigued, attentiveness begins to fade or becomes channelized. As this happens, the odds of an accident or injury taking place increases.

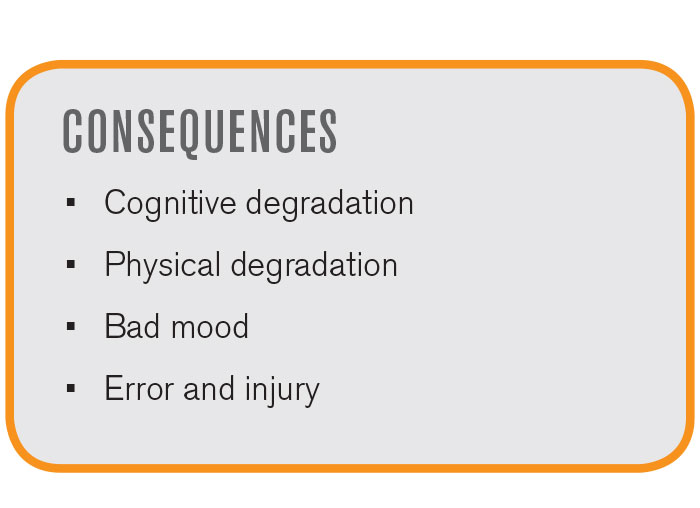

In his dissertation, Measuring and Managing Construction Worker Fatigue, Ulises Daniel Techera ranks each of the various causes and consequences of fatigue trends detected in the construction industry.

What About You?

While it can be argued that the construction industry has made many technological advancements to improve working conditions, the human condition has not changed. Workers must still keep pace with project deadlines—working overtime within long daily shifts and workweeks—making worker fatigue a deeper and more widespread condition than most employers realize.

If you haven’t already, it may be time to consider taking an innovative step in implementing a worker fatigue mitigation strategy to increase return on investment, reduce experience modification rates (EMR) and increase workplace safety. Whether you consider investing in fatigue risk management system (FRMS) software or modifying your existing risk assessment management program, your decision to address and regard worker fatigue as a viable safety hazard can be critical for your business in more ways than one.